What, in reality, does the user want form a search result? Every time we type a search term, Google has to answer the question, and it needs to get it right. It’s a complex and difficult, task. Using a mix of organic matches and a number of individually integrated features, Google’s algorithm tries to find the top matches for every type of query but how exactly does Google work out the users intention and what chances does this create for the search engine optimiser? Using an extensive set of data we’ve done an analysis.

Long-gone are the days where search results were simply ‘10 blue links.’ The list today is made up of more elements than ever before. The integration of a number of vertical searches (such as Google Images), structured data and special elements like Shopping Ads create a lot of variation in the Google search results.

In contrast to specialised search engines such as YouTube for videos or Amazon for products, the user expects the correct result for every conceivable area. To match the expectations, Google needs to be a flexible match-maker. The first stage requires Google to classify the question and in the next step it presents the right matches to the user.

What exactly does the user want? Search Intention.

When a user enters a search term in Google they have, in general, a specific question. Their expectations for the search results is dependant on the ‘intention’ of their query. In order for Google to deliver the expected results, the search process must also understand the intention behind the query. Generally we can classify the search queries into three categories.

- Navigational – The user wants to get to a specific brand or website name.

- Informational – The user wants to get information on a specific topic. In this case there are generally no commercially exploitable intentions.

- Transactional – The user is searching with the intention of doing something after getting the results. Mostly it’s a product purchase, subscription to a service or to complete a registration.

The data sources.

The following analysis is based on a data pool of 10 million keywords. Together they cover a volume of over 8 billion searches per month. The keyword selection is also representative of searches done through Google.de.

In order to analyse the SERP-Features (additional elements that appear in addition to the standard organic result) we only evaluate desktop search results, which tend to have a wider range of enhancements compared to mobile search results.

Navigational Searches

Navigational web page searches are the clearest of the search intentions: The user knows exactly where they want to go but doesn’t know how to get there. In this case the user reaches for the search engine. Search terms are mainly for brands or partly-correct domain names and URLs.

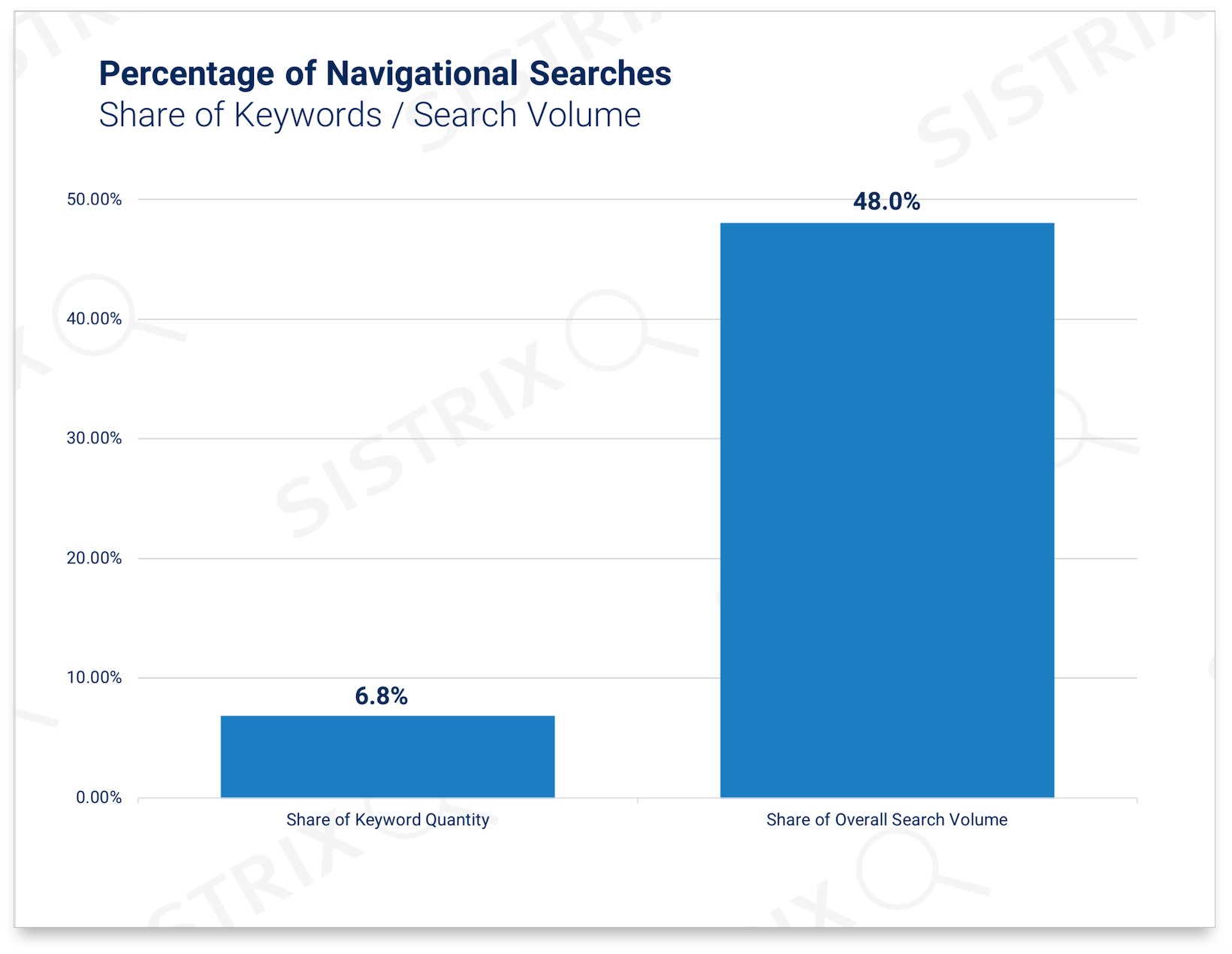

Our first analysis is based on a question. What significance do these navigational searches have within the overall search volume? In diagram 1 we analyse the percentage of all search terms that fall into this category and calculate the total search volume.

The difference is clear. Despite the fact that only 6 percent of the keywords fall into this category, navigational searches account for nearly half of the total search volume.

This huge variation clearly shows how important brands have become in Google searches.

Former Google Chairman Eric Schmidt set the scene as early as in 2008 when he said “Brands are the solution, not the problem”. It’s no coincidence that you can both search and navigate directly through the input field on every modern browser – allowing navigation to be a normal part of search.

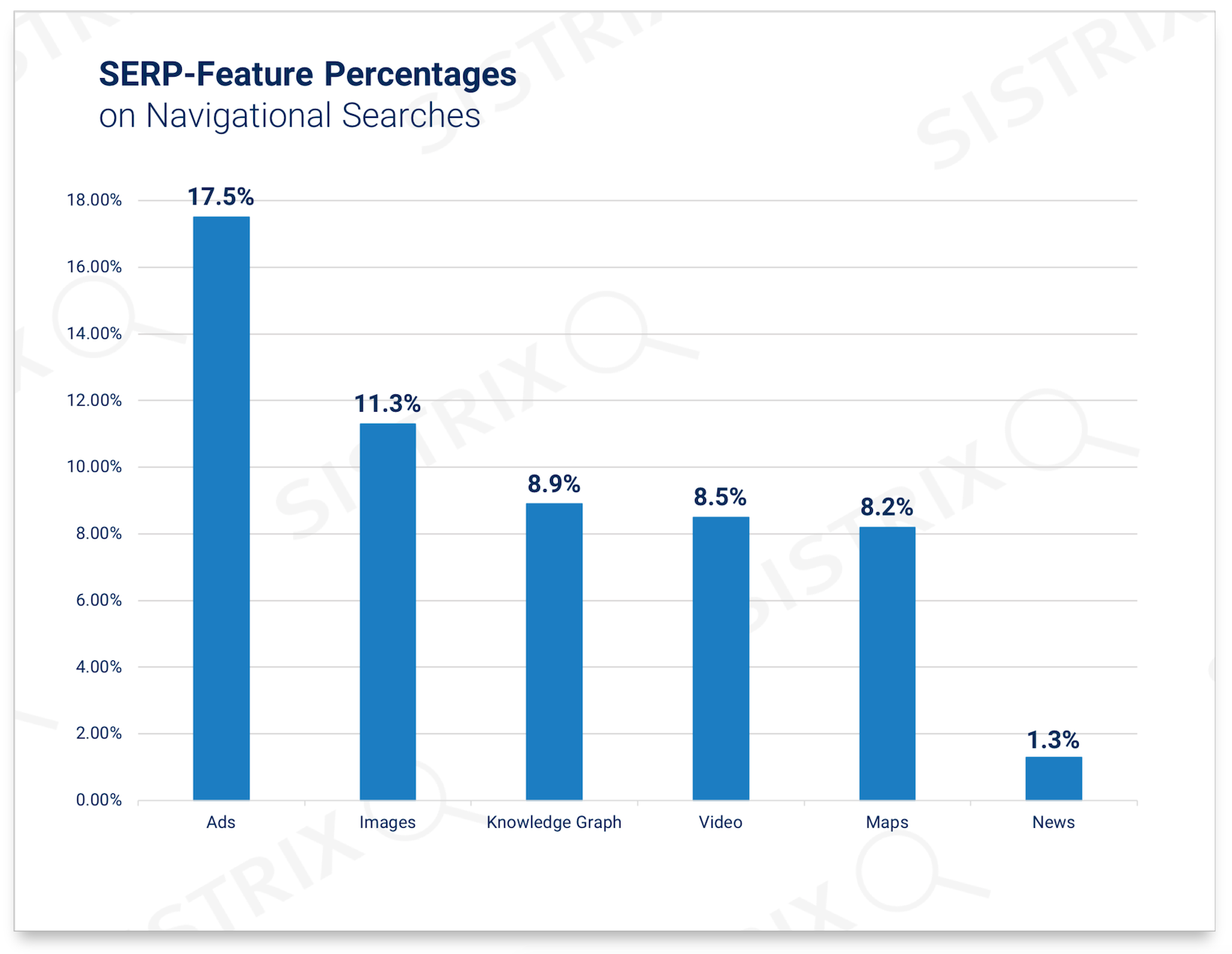

Our second analysis (Diagram 2) shows how Google integrates common SERPs-features in addition to the, mostly 7, organic results achieved through navigational searches. Despite the higher-than-average click-rate on the first result, the additionally integrated features permit at least some of the huge search volume to be exploited.

For clarity we’ve left out the obligatory sitelinks that appear in nearly 100% of cases. The most popular feature in the navigational search results are AdWords advertisements on 18% of results. Not surprisingly you’ll find companies listed for their own brands. The next most-popular features, albeit some way behind AdWords, are Images with 11%, knowledge-graph integration (9%) and then videos (9%). The integration of Google News falls way behind at 1%.

When a user searches for a brand they generally klick on that brands’ result. Yet, both images and videos are two highly visible opportunities that allow you to reach at least some of those visitors on navigational keywords for competitors’ brands, which you would normally assume to be lost.

Informational Searches

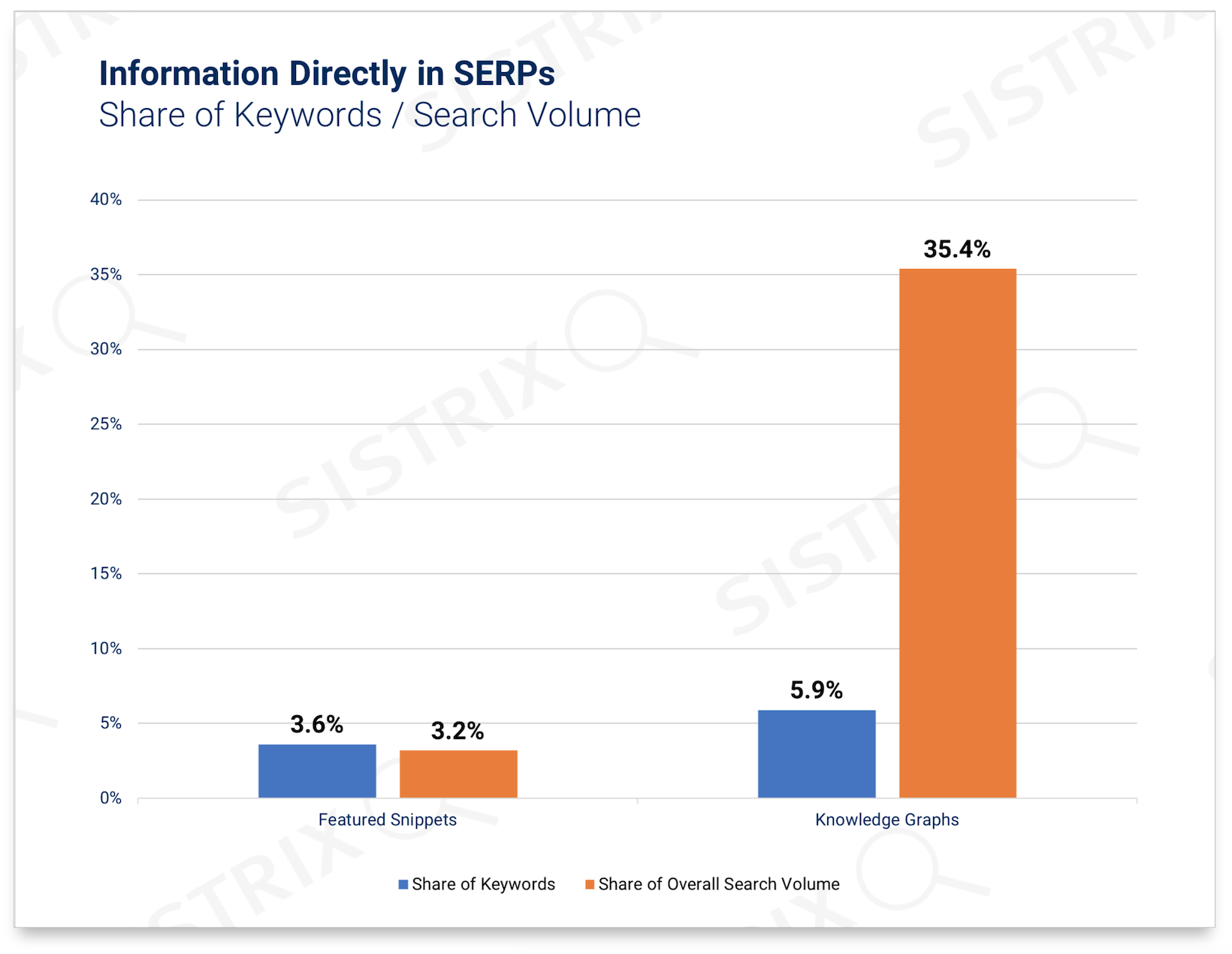

Searches that focus on the retrieval and ordering of information are the next search intention we took a look at. In recent times Google has shown keen interested in serving the searches directly in the search results pages. In diagram 3 you’ll find the evaluation of both SERPs features that serve this role.

The diagram shows the spread of Featured Snippets and Knowledge Graph integration both in relation to the keyword total and in relation to the total search volume of the keywords. The result only shows searches that don’t have a navigational focus.

Of note is that, despite Featured Snippets (3.6%) and the Knowledge Graph (5.9%) being seen across roughly the same number of keywords, many more users are going to see the Knowledge Graph. More than 35% of all searches without a navigational focus return the Knowledge Graph data directly in the search results page. Take note that, in the smartphone search results, the features are shown above the organic search results rather than next to them. In addition, you’ll only see both Featured Snippets and Knowledge Graph results together in a very small number of keyword search results.

The Featured Snippets we analysed gave us the following types:

- Text: 53%

- Lists: 21%

- Videos: 22%

- Tables: 5%

Transactional Searches

For many SEOs it’s likely that the most commercially-interesting search intention is transactional search through which money is given and taken. Similar to the informational searches, it’s not crystal clear how the categories are split – the separating lines are somewhat fluid.

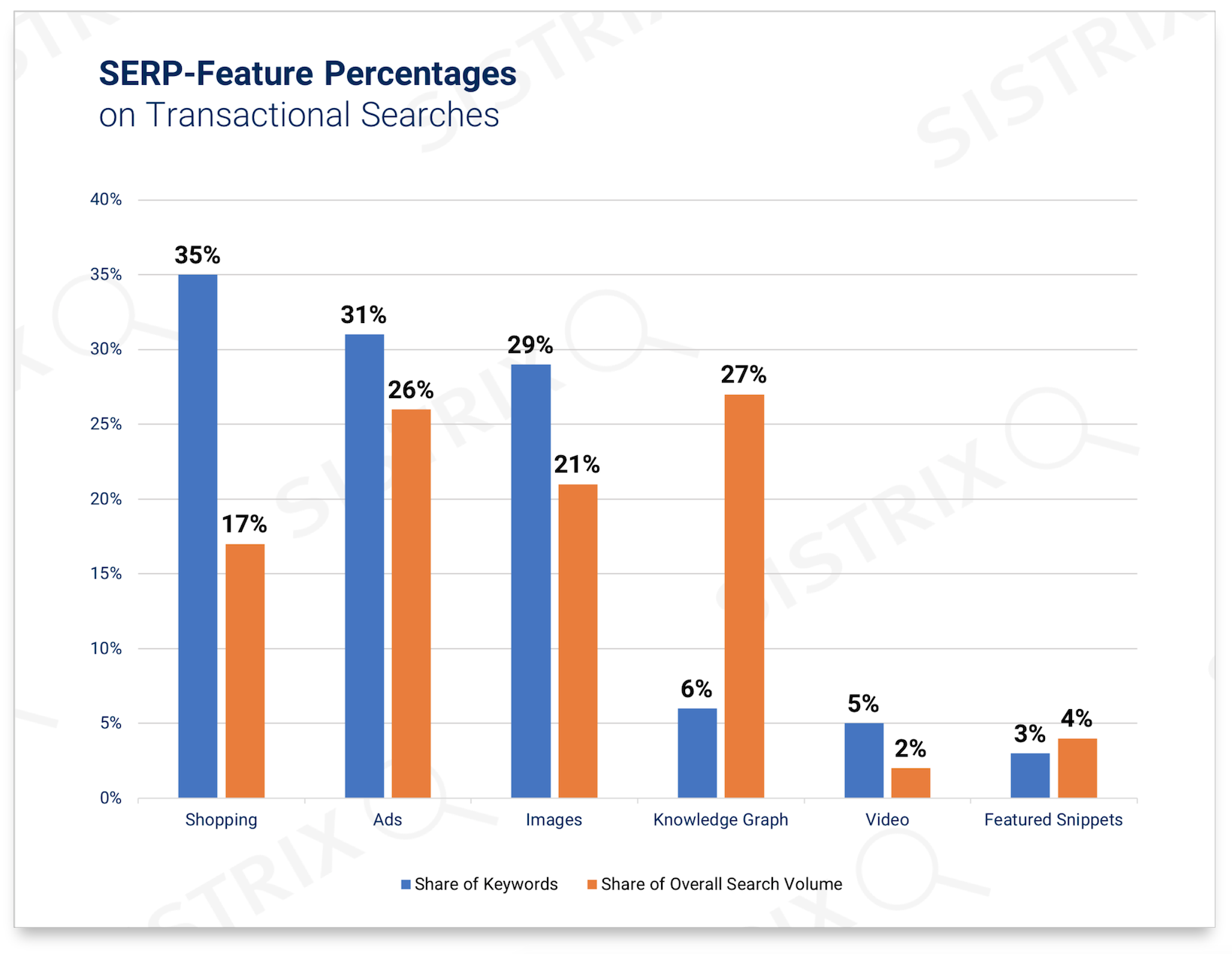

In the analysis in diagram 4 we evaluate commercially-interesting keywords that often return SERP features. We show these results in relation to both the number of keywords and the search volume.

It’s not surprising to see the commercially-focused shopping (35%) and AdWords (31%) types topping the list but shortly behind that you’ll find the Google image search results with 29% coverage. It’s clear though that the classification of search intention for Knowledge Graph boxes, videos and Featured Snippets is not as easy as expected.

No clear borders.

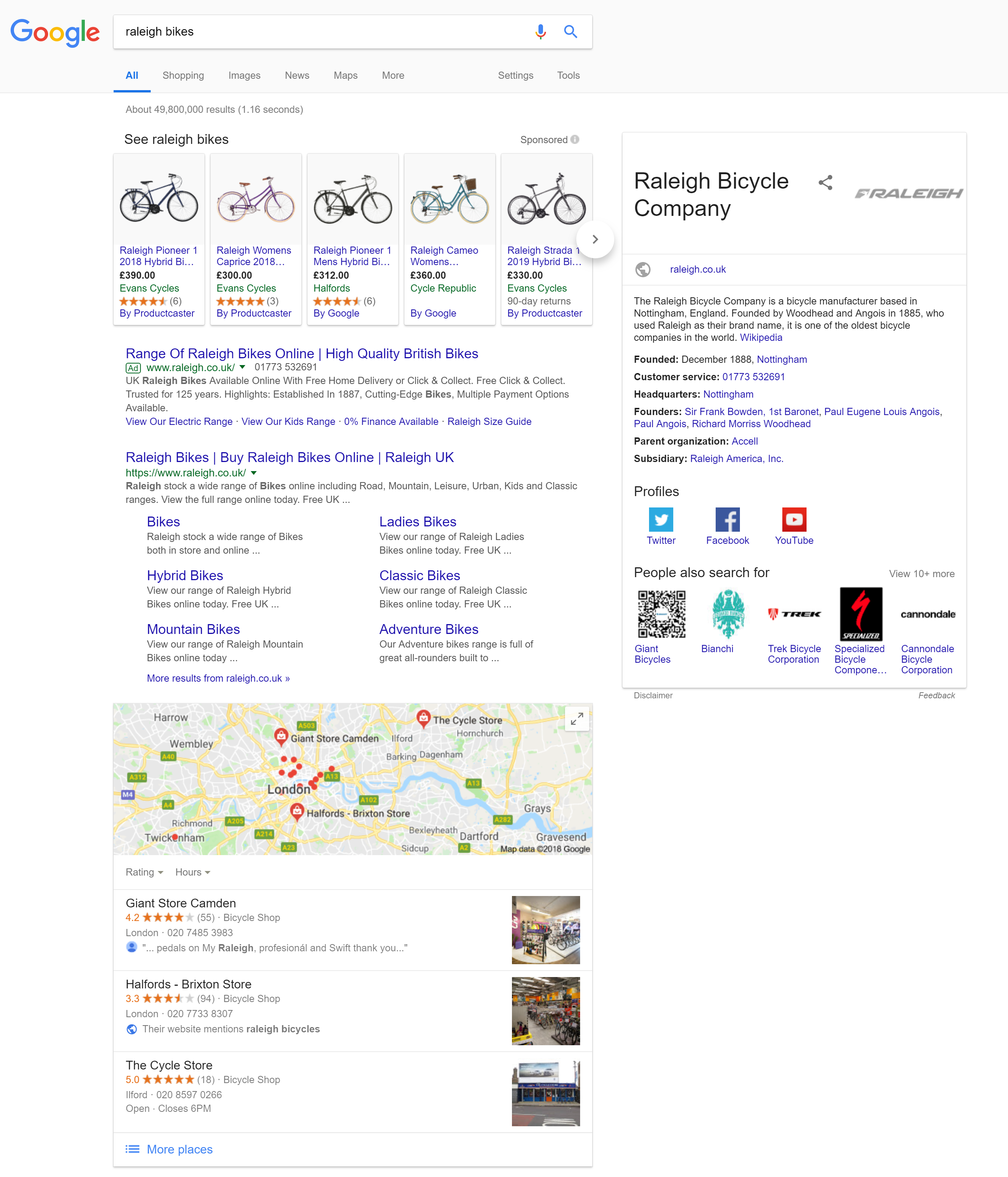

The blurred lines are demonstrated well in this SERP for “raleigh bikes” in the UK. The first organic result on this navigational search is a result with sitelinks but it also features a Knowledge Graph and above the Adwords advertising you can also see Google Shopping ads. A map results also appears under the first organic search result.

Even though this keyword search result is an extreme case, the common rule for most keyword searches is that it’s not possible to clearly define where/what the search intention is.

Summary: Google to the rescue.

Luckily, there’s Google! It’s possible to gain the important knowledge on how to correctly format a websites’ content towards a specific search intention through a deeper, detailed analysis of the elements contained in the Google search results.

Google itself uses a trial-and-error technique to collate SERPs. Through that process Google is able to learn and source the optimal contents for a results page, for every search term.

If you follow Google’s example and format the matching content on a website you’ll automatically match the search intention. The resulting positive user signals will serve to help the ranking.

However, it’s not always that easy. Matching the search intention with the corresponding website content is a dynamic process and must be checked and improved regularly. It’s sometimes also difficult to classify a search clearly into one of the three search intentions. The lines between them are fluid and constantly being adjusted.